Charging and Sentencing Trends of Criminal Tax Cases

The U.S. Sentencing Commission, which provides sentencing guidelines, collects substantial amounts of information on sentencing, including dozens of data points for every criminal case. The data are publicly available, permitting an analysis of specific categories of crimes, including tax crimes.

by Jed M. Silversmith, JD, and Miranda A. Galvin, PhD Jun 4, 2021, 15:22 PM

Maybe it’s

not as philosophical as, “If a tree falls in the woods and nobody is there to hear it, does it make a sound?”, but the question that vexes tax professionals is, “How false does a tax return need to be before a taxpayer might

be charged with a tax crime?” It is not always clear.

Maybe it’s

not as philosophical as, “If a tree falls in the woods and nobody is there to hear it, does it make a sound?”, but the question that vexes tax professionals is, “How false does a tax return need to be before a taxpayer might

be charged with a tax crime?” It is not always clear.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission, which provides sentencing guidelines, collects substantial amounts of information on sentencing, including dozens of data points for every criminal case. The data are publicly available, permitting an analysis of specific categories of crimes, including tax crimes.

- More men are charged with tax crimes than women, but tax fraud cases constitute a larger share of crimes for women than other offenses.

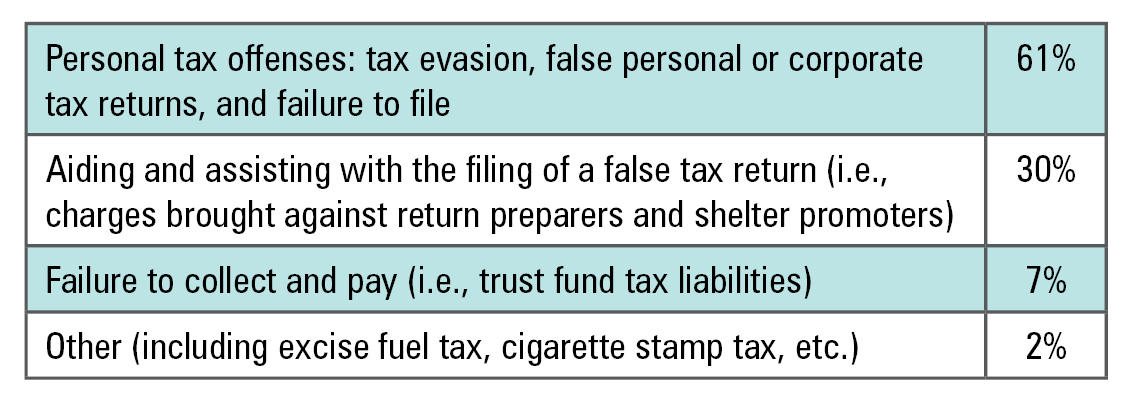

- Most individuals charged with tax crimes are charged with crimes involving their personal tax returns.

- Tax defendants were more likely to be White (50.1%), nearly 20% higher than African-Americans (30.9%).

- Over 80% of cases involve multiyear tax liabilities, totaling between $40,000 and $1.5 million.

- Over 90% of cases result in guilty pleas.

- The overwhelming number of defendants who pleaded guilty received sentences below the Sentencing Commission’s standard recommendation (the “guideline range”).

Tax Charges Pursued

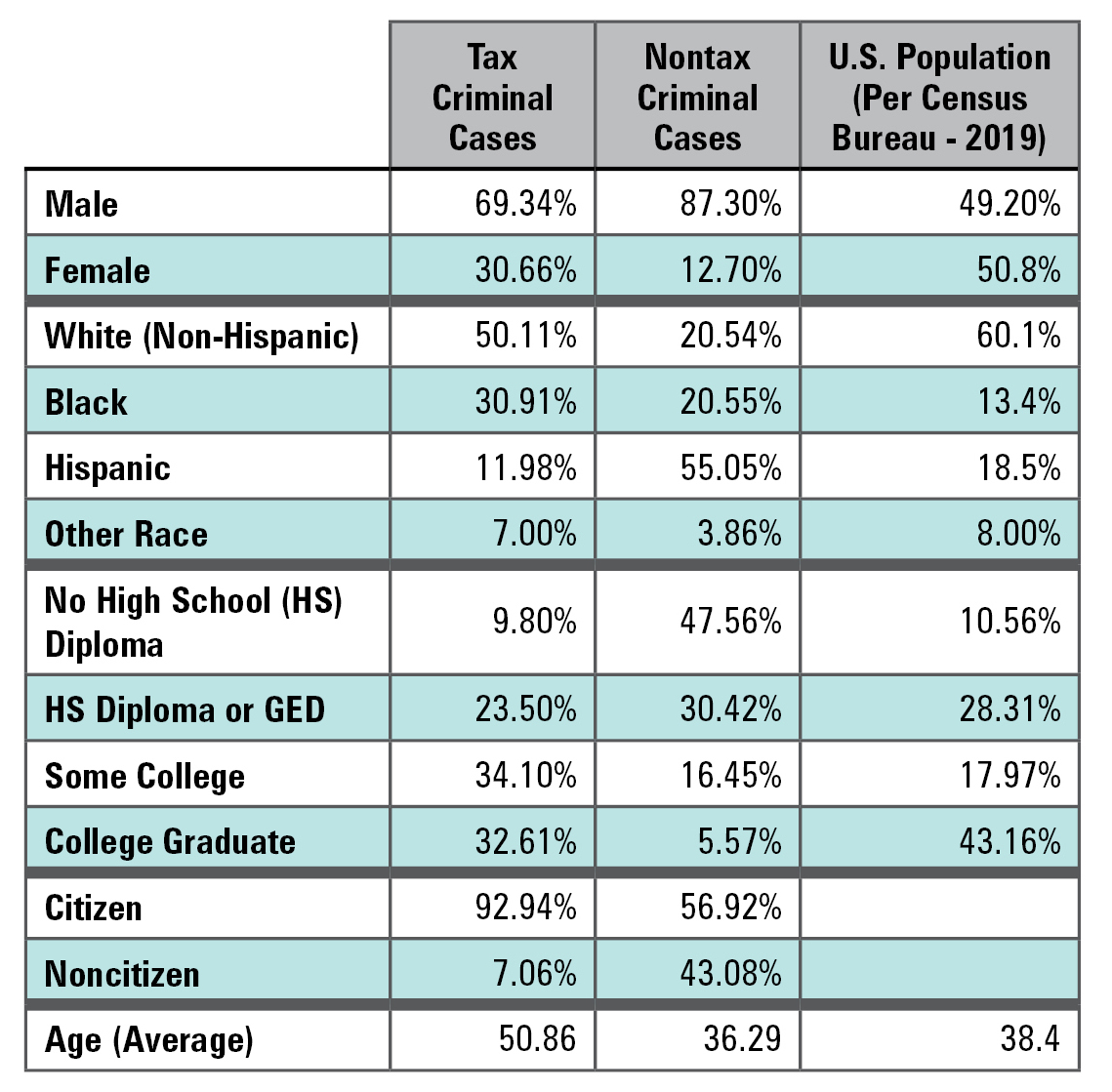

Demographics of Tax Defendants

We compared the demographics of individuals sentenced in tax cases to individuals sentenced for all other federal offenses and the general population. Men are more likely to be charged with tax crimes than women; however, the proportion of female defendants is higher for tax crimes than other offenses. Criminal tax defendants are more likely to be non-Hispanic, and far more likely to have attended college relative to defendants for other crimes. Further, defendants in tax cases were substantially older. The majority of tax defendants were White (50.1%) while being 60.1% of the population; African-Americans were nearly 40% of tax defendants but represent 13.4% of the population.

Sentencing Trends

Standing accused is one thing, but the sentences imposed in tax cases may be more interesting. The determination of sentences for federal offenses is complex.

In the federal system, recommended sentences are based on the seriousness of the offense and an individual’s prior criminal history. Among the reasons for enacting the sentencing guidelines were to ensure uniformity and increase penalties for white collar offenses.2 When a defendant pleads guilty or is convicted at trial, the Probation Office prepares a presentence investigation (PSI) report. To determine the offense level in tax cases, the Probation Office first computes the “tax loss” or the amount of tax due and owing. Estimates of tax loss are critical; they reflect the harm to the government, and harm to the government is a factor at sentencing.

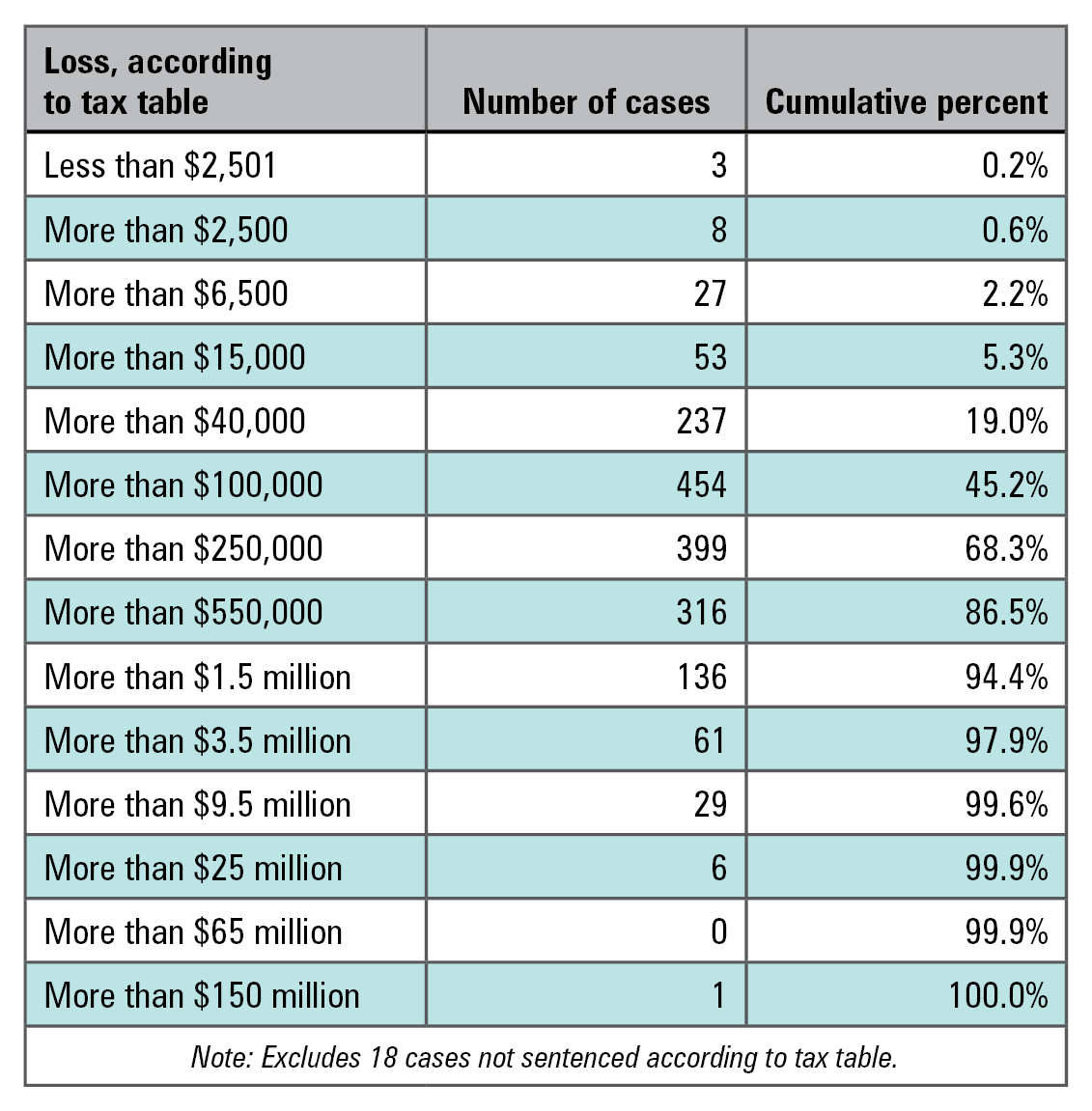

District courts generally apply the term “tax loss” broadly. For example, the government is not bound by statutes of limitation. This means that if it possesses sufficient records, the government is permitted to compute a tax loss figure outside the six-year statute of limitations usually applied in civil audits.3 Also, state income tax liabilities may be included in the tax loss calculation, as can self-employment taxes. Except in instances where the defendant has tried to evade the payment of already-assessed tax liabilities, the government does not include interest and penalties in tax loss. In cases where a defendant proceeds to trial and is acquitted of some charges, the district court may still include the acquitted component as part of the tax loss calculation. The tax loss figure almost always represents several years of tax due and owing, and rarely represents one year’s tax liability. However, most cases brought have relatively low levels of tax loss. Almost half of all cases have tax loss figures of less than $250,000.

Once the Probation Office computes the tax loss, the offense level is adjusted upward or downward based on several factors, including the following:

- Did the defendant fail to report over $10,000 in income from an illegal source?

- Did the defendant use “sophisticated means” to conceal tax due and owed?

- Was the defendant in the business of preparing tax returns?

- Did the defendant demonstrate acceptance of responsibility and plead guilty?

The final offense level is then cross-referenced with the defendant’s criminal history, yielding a recommended sentencing range.

Among the guidelines we analyzed, defendants who had a tax loss between $100,000 and $250,000, had no prior criminal history, and received no additional enhancements received a recommended guideline range of 12 to 18 months if he or she pleaded guilty.4 Defendants with the same profile who did not plead guilty and were convicted at trial received a recommended guideline range of 21 to 27 months. In both instances, the guidelines recommend a term of incarceration.

After the PSI is prepared, the district court conducts a sentencing hearing during which each side may challenge the Probation Office’s findings. Depending on the complexity of the tax issues, each side may call experts to testify. The district court then adopts or modifies the PSI and proceeds to sentence the defendant based on the final calculations.

As a result of the 2005 U.S. Supreme Court decision United States v. Booker, sentencing guidelines are advisory rather than mandatory, and district court is not required to impose a sentence within the guideline range and may vary from the recommended sentence.5 Scholars have noted that these variances may create opportunities for sentencing disparities, but such sentences have generally withstood appellate scrutiny.

In one case, the government appealed a downward variance that had permitted the defendant, a plumbing contractor, to serve a house arrest sentence within the extravagant home he had remodeled: the irony being that the defendant’s deduction of the remodeling expenses on his taxes was the substance of the tax scheme. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals issued an en banc opinion (a decision issued by all 13 judges of the court, not just a panel of three judges) that affirmed the sentence of house arrest based on a $228,557 tax loss. 6 In the majority opinion written on behalf of eight of the 13 judges, the court noted that although they may have personally reached a different result if they had sentenced the defendant, the test for appellate review is not “disagreement,” but whether the decision was “unreasonable.” This is a high bar, and as a result a district court has broad discretion to impose whatever sentence it deems fit.Conviction and Sentencing

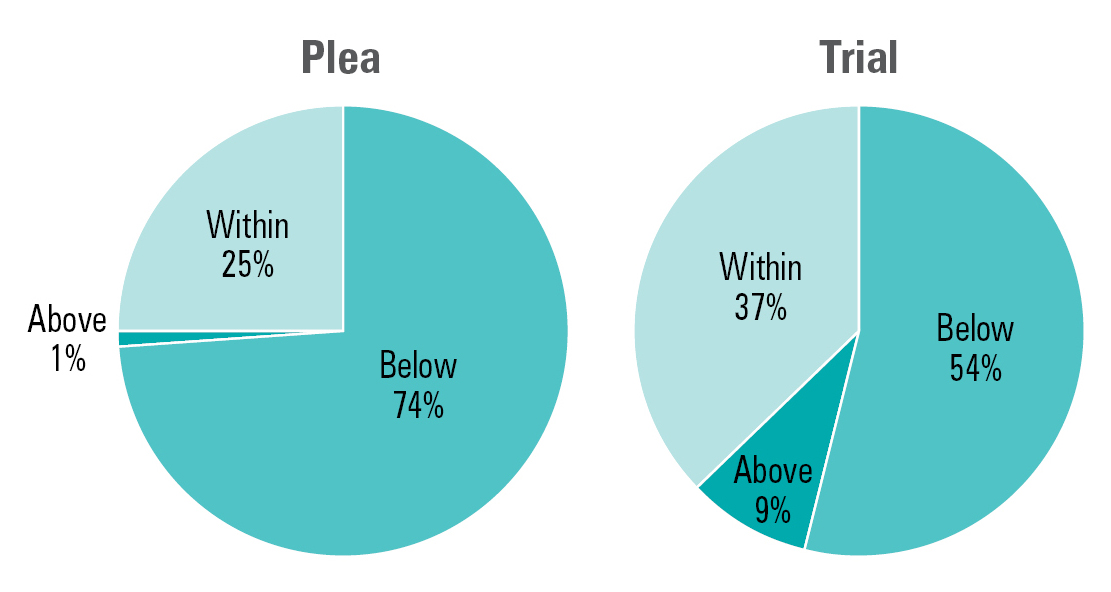

Of the 1,748 cases in our sample, only 127 (7%) were convicted by jury trial; the remaining 1,615 (92%) resulted in guilty pleas.7 Intriguingly, only 25% resulted in a sentence within the recommended guideline range. Thirty-three cases (1.9%) resulted in sentences above the recommended guideline. The rest (about 73%) resulted in sentences below the guideline.

Where the defendant’s tax loss calculation exceeds $100,000, he or she is supposed to receive a term of incarceration under the sentencing guidelines, even if pleading guilty (although a judge may vary downward and impose a noncustodial sentence). Only 58% of the defendants who pleaded guilty and had a tax loss of between $100,000 and $250,000 received terms of incarceration. As the guideline range increased, the ratio of defendants who received terms of incarceration increased. Thus, defendants who pleaded guilty with a tax loss of between $250,000 and $550,000 received terms of incarceration 72% of the time; in cases where the tax loss was between $3.5 million and $9.5 million, and resolved by plea, the sentence was custodial 87% of the time.

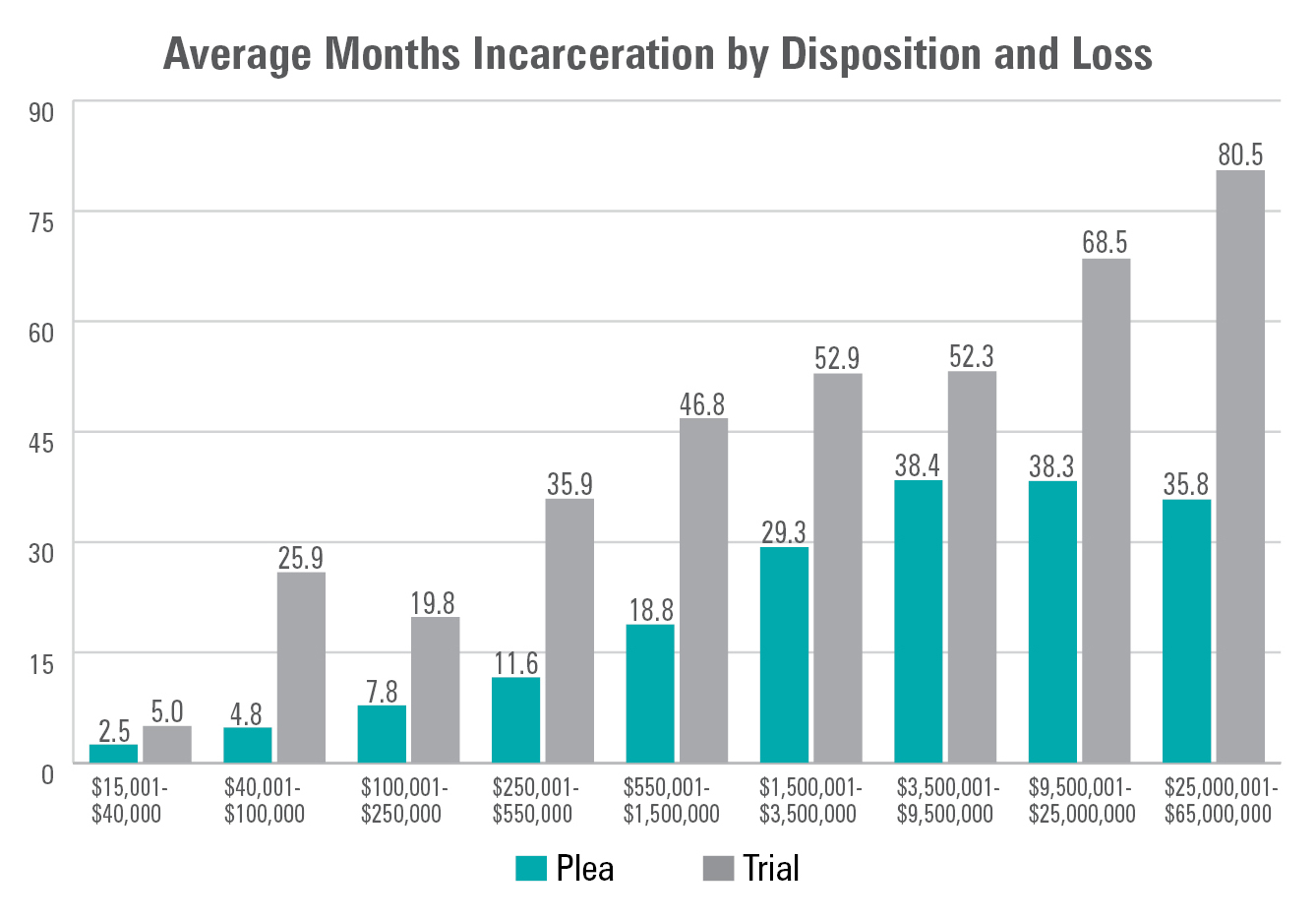

Among individuals who were incarcerated, those who pleaded guilty received better sentencing outcomes on average than those who proceeded to trial. Consider the graph on page 25, which depicts the average sentence length (in months) among defendants who were incarcerated by tax loss and disposition. In general, sentences increase as tax losses increase.

Note: we have not discussed very low tax loss or very high tax loss cases in this analysis. There were 91 cases (89 guilty pleas and two trials) where the tax loss was below $40,000.8 The government also brought 18 cases where no tax loss

was computed (15 of these cases were smuggling cases, not income tax cases). On the other end of the spectrum, there were seven cases where tax loss exceeded $25 million. These cases are atypical, so we did not include them in our analysis.

Another factor to consider is the relationship between sentences given and the recommended guideline range. The graph below depicts the prevalence of above, below, and in-range sentences. We do not depict these patterns by loss, as most defendants

receive below-range dispositions regardless of tax loss. As shown, we continue to see a sentencing advantage to cases resolved by plea: 74% of those resolved by plea receive below-range sentences compared to only 54% of those resolved by trial.

The Illegal Source Enhancement

One of the oldest clichés is that Al Capone made the IRS famous. In 1962, the U.S. Supreme Court held that embezzled money constitutes gross income.9 Since that time, federal prosecutors have used the tax evasion statute and the charge of filing a false income tax return to prosecute embezzlement schemes that do not otherwise violate federal law. Under federal sentencing guidelines, a defendant’s sentence is increased if he or she fails to report $10,000 from an illegal source in a given year. Sentencing data reveal that this enhancement was only imposed in 18.93% of the cases, suggesting the IRS spends most of its effort pursuing “legal source” cases.

Conclusion

These statistics show that even a small amount of tax loss can lead to criminal prosecution, though the likelihood of being charged with a tax crime is low. Still, the IRS does pursue low-dollar tax crimes. Defendants who plead guilty receive far milder sentences than those who proceed to trial. On balance, though, even those who proceed to trial frequently receive below guideline sentences.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top